|

|

Kuo Jing's Journal: Singapore

11 September (Day 47)

At this morning’s meeting, the Abbot said some very important words. We record them for posterity:

“Yesterday, while talking to the Youth Buddhist Association, I told them that after I die I want my body to be burnt. My bones and ashes should be ground to a powder, rolled up with flour, sugar, or honey, and fed to the ants. Why? Because I’ve called myself an ant, and I have great affinities with ants. After having made a meal out of me, they should quickly resolve on Bodhi.

Now that I’ve made this decision, make sure that you follow my instructions. When the time comes, I don’t wish to leave any trace behind.

Sweep clean all dharmas, separate from all marks.

I don’t wish to leave a flesh body behind like the Sixth Patriarch or Dharma Master Tzu Heng. I don’t want any stupas or memorial hall built in my memory.”

Someone asked whether the Elder Hsu Yun’s ashes were actually mixed with sugar and flour and rolled into pellets to feed to the fish, as was his wish. No, his disciples could not bear to part from their maters’ remains, and so they housed the ashes in shrines instead. Yet in doing so they did not comply with the Venerable One’s wish.

“Why do I specify this request? Because not many people believe in my giving away the City of Ten Thousand Buddhas to the entire world. They can’t believe that there’s someone whose only aim is to benefit all beings. I’ve given the City of Ten Thousand Buddhas to everyone in the world, not just to Americans or Chinese, not just to Buddhists, but to all living beings, people of all other religions as well. I’ve observed the causes and conditions of Buddhism, and only through a dynamic act of selfless giving can Buddhism be saved. Otherwise it will surely die. So in the future, nobody can lay private claims on the City of Ten Thousand Buddhas or any part of it. it will forever remain public property of World Buddhism … what do you think?”

A hushed silence. Bathed in the quiet morning light the nine of us listen transfixed by words that flow out from a mind that is beyond ordinary conception, beyond all measure or comparison.

“The only people who are allowed to run the City are people who are selfless, people who truly practice the Bodhisattvas conduct of benefiting all. It cannot be used for private gain or benefit. I told you last night that if I have a single hair’s worth of selfishness I’m willing to forever stay in the hells. Always give away the good things to others, don’t hoard them for yourself. Don’t seek name or recognition. And above all don’t be jealous and obstructive. Whoever is better than I, I respect that individual but will never obstruct him.”

Somebody comments on the uproarious reaction at last night’s lecture: some Sanghins walked out, but the lay people cheered and clapped. The Abbot says,

“The cheering was also not in accord with Dharma – I told people that this is no laughing matter. The very survival of Buddhism is at stake. Not only should Sanghins not keep private assets, even lay people who dedicate their lives to Buddhism shouldn’t keep private assets. Otherwise a very imbalanced situation will appear with all the money concentrated in the laypeople’s pockets. This campaign against burning incense and paper is just paving the initial steps of the revolution. As we gather momentum there will be a much wider sweep of things. The custom of reciting the Sutras for money will be abolished, for example. Right now this ritual serves as bread and butter for most of the Sanghins in Asia, plus a lot of lay Buddhists as well. But the time isn’t ripe; if I were to tell them now, they wouldn’t be able to accept it.

The Sanghins in China used to be largely uneducated. For all the wealth each temple amassed, there were no Buddhist schools – no elementary schools, no high schools, not even one Buddhist university throughout the entirety of China. I’ve seen temple treasuries loaded with gold bars, with their weight in tons in fact, yet people were selfish, hoarding it for themselves, not spending it to help Buddhism thrive. That is why I say I am not a temple builder. Yes, I am an artisan, but instead of working in gold, wood, clay, or stone, I hone Buddhas, Bodhisattvas, Patriarchs, and Arhats out of living flesh.

All our efforts should be expended on education. If you Americans are going to build in the future, don’t just build temples; build schools. Every school should be equipped with a large lecture hall which can be used for all purposes: worshipping, reciting, Dharma assemblies, and lectures. Building educational institutions is my wish. No matter where I do, I speak from my true heart, and there’s no way people won’t be moved. Not only people, even wooden stumps and rocks will bend to the sound of true Dharma.”

Watching the example that the Abbot sets at every moment leaves us with great shame. The solution is not to wallow in this shame, but to seriously get to work.

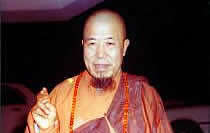

At lunch Bhikshuni Hui Shen joins us. She’s been translating the Abbot’s instructions into beautiful Fukienese so that night after night people can listen with unobstructed pleasure to the Dharma rendered in their own dialect.

Gauntly built with ascetic features, Bhikshuni Hui Shen is an unusual gem in the Sea of Buddhists we encounter every day. Her keen sense of carriage attests to fifteen years of hard cultivation. A native of Taiwan, she had left home under the Venerable Chu Yun, and six years ago came to Singapore to propagate the Dharma. While still a lay people, she started a radio program on Buddhism about fifteen years ago in Taipei; the program received such favorable reviews that it was extended from a once-a-week format to an hourly program every day. She has continued vigorously in lecturing the Sutras and teaching Dharma classes ever since.

Seeing the degenerate state of Asian Buddhism and the disorganized Sangha,, Dharma Master Hui Shen shakes her head. With an intensity of belief in her voice she says,

“If we are selfish and squabble among ourselves, or cater only to appearances with no thought for actual cultivation, how can we merit the name of left-home people?’

She admits that during her six years in Singapore she has not been a favorite among the local Sanghins. Instead of conforming to the usual practices of her peers such as reciting Sutras for money or being too chummy with Dharma protectors, she prefers quiet, hard work in her milieu. From the few days I’ve had a chance to observe her, there seems to be a core of lay disciples, old and young alike, who have a deep and wordless faith in her. She says at lunch,

“When we see these beings suffering so miserably, how can we fail to bring forth compassion? I’m just a Bhikshuni with little status, yet for as long as I have a single ounce of strength I must dedicate it to the revival of the Dharma.”

Heng Hsien and I have felt an instant admiration for her, and the Abbot is, as usual extremely kind. He says matter-of-factly.

“This Dharma Master was a fellow cultivator with Kuo Jing in their past lives, which is why they discover such instant affinities. So many of my disciples get scattered over the world when they receive another birth, but bit by bit, all of them return to base camp.”

After lunch we have a little chat. In a quiet place Bhikshuni Hui Shen smilingly confides in me,

“Do you know, I’m wearing the absolute best robe I own. I have only two robes that I wear to go out with. The rest of them are tattered and patched up, and I prefer it this way. People give me cloth and robes, but I give them away as quickly as they come. Why? I don’t deserve to wear good clothes, plus it’s just extra burden when I pack up to go. I ask my friends, ‘Do you come to hear me because I wear well-tailored robes, or have we come to investigate the truth together?’ usually they pipe down after this.”

At seven there is a refuge ceremony. Over six hundred take refuge. In a while the Abbot gives instructions,

“It’s said that in a single day it is easy to sell ten bushels of the false, yet in ten days it is hard to buy one bushel of truth. Many people believe in the false, and very few believe in the true. This is due to our habit from beginningless kalpas, that of mistaking suffering as bliss. Everything I say to people is false. Why? Because you cannot utter the truth. All marks are false and empty, all words are false and empty. When the point is reached that the path of words is cut off, and the mind’s activities cease – only there can you find truth. Yet right within the false is the truth, and right within truth is the false. True and false do not obstruct one another, they are interpenetrating.

Also, truth is not true of itself, and the false is not false of itself; rather, it is living beings who make it either true or false. Living beings are just Buddhas, sages, and gods. Living beings are temporarily attached to confusion and turn their backs from enlightenment. Once the confusion is peeled off, enlightenment is revealed therein: it is at no other place. Disregarding our family treasure we have become prodigal sons, willingly shuffling waste and collecting garbage. Wouldn’t you say this is a pity?

If you want to find the truth, just don’t do anything false. This means in every gesture or word, do not be false.

The path comes from practices;

Without practice there is no path.

Virtue is cultivated;

Without cultivation there is no virtue.Merit is established on the outside,

Virtue is developed inside.

If you establish merit on the outside,

Your virtue inside will abound and

_ you will be filled with your original wisdom and Dharma bliss.The T’ang poet, Han Yu, said in a few lines from his essay, the Original Way:

Humanness is universal affection; righteousness is appropriateness in action; going from here to there is the Path; virtue is contentment with oneself and not relying on outer resources; the heart is the root of humaneness, righteousness, principle and wisdom. This produces a glow that naturally flushes one’s skin, lights up one’s arms, and infuses one’s four limbs. The four limbs thus speak without saying a word.

In fullness there is beauty; in fullness and light there is greatness; greatness transformed is sageliness; sageliness which knows itself becomes godliness…

“Han Yu’s essay can be applied to cultivation. When you have universal concern for all, just this is humaneness; if you behave properly for every occasion, that is righteousness; going from here to there is traveling on the Way; possessing virtue just means embracing loyalty, humanness, reason, and wisdom. Then a glow will exude from your entire body. People who cultivate have a lot of light about them. The harder you cultivate, the more light you have and your light speaks without need for words. When you truly fortify yourself with Way virtue, you’ll achieve beauty, greatness, sageliness, and godliness.

When you are in total communion with these states, you have achieved your heart’s desire, without having in the least bit transgressed the law of heaven and nature. Confucius put it this way:

At fifteen I resolved on learning. At thirty I stood firm. At forty I was no longer confused. At fifty I understood the decree of heaven. At sixty my ear was an organ for the reception of truth. At seventy I could do whatever my heart wanted and yet not transgress propriety.

“When Confucius said that at sixty his ear was the organ for the reception of truth, it meant that whatever he heard was in accord and was pleasant. Only at seventy was he able to freely do what his heart desired and yet never transgress the proper. What a liberation that is! It is just recovering the spontaneous, divinely innocent quality in our nature. People who wish to study Buddhism should first learn to be good people; do not do things that only benefit yourself but harm others.

Now Tao Yuan Ming, the famous fourth century pastoral poet, was famous for his lofty character. He gave up a high governmental post because he would not bend to protocol and bureaucracy, but preferred to live blissfully in communion with Nature. in the Ode of Return he sings:

The fields have grown wild.

Why do I not return?

My heart has been enslaved by my body,

How can I not lament in lonely sorrow!

Understanding my past faults,

I know that I can make amends for the future.

Not having gone too far down the deviant path,

I awaken to today’s right and yesterday’s wrongs.This poem is well-tuned to the Buddhist’s heart. When we say, ‘The fields have grown wild,’ it can refer to our mind-ground which is thick with the weeds of ignorance. We should quickly return to the Western Land of Ultimate bliss. Then we can turn the boat around and save the beings in the Saha world. Our mind has become a captive of our body and we have no real mastery over things. This is, or course, a state worthy of remorse. However, upon understanding mistakes we’ve made in the past – as Confucius said, ‘Having reached fifty, I know my errors of the past forty-nine years’ – we should then look forward to the future and make amends. There’s still hope. What’s right today is studying the Buddhadharma; what was wrong yesterday was throwing your life-force away. Another poem says,

If you do not seek the Great Way to leave the path of confusion,

Despite blessings and worthy talent you’re still not a great hero.

A hundred years is but sparks struck from a rock.

A body is a bubble bobbing in water.

Wealth will be left behind; it doesn’t belong to you.

Offenses follow you and it’s hard to cheat yourself.

With gold piled high as a mountain,

Can you bribe impermanence when it comes?If you do not seek to leave the dust, however many talents and worthy skills you possess will still be in vain. Don’t be too smart for your own good. Why don’t you use your intelligence to cultivate instead? Even with profuse erudition and a stomachful of learning, you still don’t figure as a great hero. A great hero is one who transcends the performance of his peers; he has impressive vision and prowess. Time flies by in a flash. Don’t think this money, this pretty wife, these houses and cars are yours – you can’t take them with you when taken refuge time comes for you to see King Yama, you can’t bribe the ghost of impermanence, even with your mountains of gold and silver.”

Day by day the audience increases its receptivity; the revolution has begun. The seed has been planted. Daily it grows and flourishes.

12 September (Day 48)

Kuo K’ung leaves this morning to go back to Alabama to resume his teaching post. University courses start in a few days. We have lost one very important member of our group.

From outside comments, it seems that, along with the Abbot, Professor Yu Kuo K’ung has exercised a tremendous influence upon the people here. His appeal to young people and the academic community is far-reaching. University students, Professors, scholars, and other professionals who would never have believed in Buddhism are now drawn in because of the principles that Kuo K’ung expounds. The Abbot speaks highly of him often, and this morning after Kuo K’ung’s departure he says,

“He is singly the most forceful personality in this group. He has a vast, broad mind; everything is open with him. This is the uprightness of a great hero who works for the benefit of all. In all things you should keep your eye on the entire picture, the larger scope. There’s no room for petty concerns about one’s own been fit. Don’t be one who thrives on eating, sleeping, putting on clothes, and spends the rest of the time being jealous and obstructive.”

Heng Sure remarks – and everyone agrees – how extraordinarily smooth everything has gone since the beginning. The road is paved, and all we’ve needed to do is walk on it with our gaze fixed straight ahead. Making allowances for occasional differences in personal opinions, at no time have there been the major blow-ups, mutual distrust, or accidents that mar most delegations. The Abbot says,

“For all the days we’ve been here it has not rained once before or after the lecture when people are coming and going. If you still do not understand to what an incredible degree the gods, dragons, and others of the eightfold division are supporting the Dharma, then you have really missed the message.”

Tonight is our last evening in Singapore. Due to many people’s requests we hold another refuge ceremony in the jam-packed hall. Out of the entire lecture-time, the Abbot speaks about fifteen minutes. He lets every member of the delegation talk. Some of us choose to relate a few of the inconceivable happenings that frequent the community of cultivators at the City of Ten Thousand Buddhas and Gold Mountain Monastery.

The fact that the Abbot has on innumerable occasions commanded the weather is well-known to all Gold Mountain adepts. One example is the World Peace Gathering held at Seattle, Washington, in 1974. it had been raining non-stop all along the West Coast, but the Abbot announced that he would “not allow” it to rain at the three-day gathering. One this occasion, Kuo Kuei took a plane from San Francisco to Seattle. He rode through black clouds and stormy weather that was driving rain from the southern United States coast all the way up to Canada. From the plane he saw a bright ring of blue sky miraculously hovering over the city of Seattle for a radius of about twenty miles. Clear skies prevailed for the entire three days of the gathering, whereas stormy weather hit all the neighboring towns. “When a Way Place practices the Proper Dharma, the gods and dragons and guardian spirits come to protect us and incredible states become common occurrences,” Kuo Kuei concludes.

I speak of a dream I had years ago. I had come with my family to a place that looked like a paradise right in the real of people, an out-of-the worldly Shangri-la. Perched on a high plateau among green and violet hills, where dragons and unicorns cavort in sailing clouds and running brooks, is a large temple complex housing several thousand people. The architecture is a quintessence of Eastern and Western cultures, a style which is unique. As the bells and drums resound throughout the entire city, thousands of yellow-robed Sanghins stream from their cubicles, as well as lay people of all colors, races, ages. In front of the assembly walks an elderly Chinese monk whose awesome comportment immediately commands veneration. I remember his small, wispy beard most clearly.

Not until years later, after I have actually arrived at the City of Ten Thousand Buddhas did the dream come back in its magnificence.

One morning, soon after my arrival at the City, I walked up to a hilltop overlooking the valley. Here from a viewpoint nestled among ancient cypresses and pink maples, one can enjoy panoramic view of the expansive horizon, the rolling hills, and the orchards and vineyards in the valley below. The hills were lavender and blue, and trails of swirling mist hugged their curves. The sun was breaking through a sea of clouds. A wild goose’s wail pierced the silence. Suddenly the dream in its full glory came back in a flash and hit me like a giant wave. Tremors were running up and down my spine; I realized that I had come back. This place was bequeathed to us many, many aeons ago. Upon awakening lifetime after lifetime, we continue to realize the promise. It is the home of ten thousand living Buddhas.

Heng Hsien talks about the Abbot’s prediction that she would qualify in her PH.D. examination before she ever took it. Another story about manning the weather for our benefit: a group from Sino-American Buddhist Association had gone to New York in the winter of 1973 for a conference. There was a raging blizzard and conditions for driving on the road were treacherous. The Abbot entrusted a disciple to take charge of the snow; no snow was allowed to block the group’s passage. And, sure enough, wherever they drove on the highway there was a clear patch right around them for a radius of two or three miles, while the surrounding area snowed profusely. Now, how did this work? The Abbot reveals with amusement that he had previously given his disciple an ultimatum. If this disciple could not manage to keep the snow at bay, after they returned to Gold Mountain he would have to kneel in front of the Buddha images for forty-nine days, without ever getting up, with no food or drink, not even a chance to go to the toilet! This scared him into praying most sincerely to the Buddhas for aid. The result was a remarkable response.

The last one to speak is Heng Sure. He has a piece of small news and a piece of big news. The small news is that some lay people have been able to kick a chronic smoking problem ever since they heard the Abbot speak out strongly against the habit. Smoking not only breaks one of the five precepts, it wrecks one’s body and the environment. Upasika Huang Cheng-Chao from Taiping, who has averaged fifty cigarettes per day for thirty-odd years, decided to really quit after he heard the Abbot speak. The next day he simply stopped. A month has passed and he hasn’t lit up once. Instant result: rosy cheeks and a big bright smile.

The big news concerns the comet Kohoutek. When it surfaced in the corner of the sky about five years ago, most unwary scientists thought it was an auspicious portent. The reverse was true. Whenever comets of this sort appear they signify impending disasters; they arise due to the sum total of evil karma created by mankind. Millions of people would have been killed if this comet had collided with the earth or had been drawn into its gravitational field. The Abbot announced to the Dharma assembly at that time, “The only way to avoid this disaster would be for someone to take on a strong bodhi resolve to avert the calamity for the sake of the entire world.” Several months later a Bhikshu commenced on a journey, bowing once every three steps from San Francisco all the way to Seattle, a journey of over a thousand miles. Another Bhikshu vowed to be his Dharma protector. As they were bowing, daily the comet drew nearer to the earth’s orbit. On the one hand, scientists were confidently predicting the comet’s arrival, on the other hand, two cultivators backed by a whole community were trying their best to drive the comet away!

About a month before the comet actually withdrew, the Abbot announced one night at the assembly, “I have some good news for you. The comet is going to go back.” Sure enough, a month later, just as it was nearing the earth, Kohoutek suddenly retreated, disappearing as mysteriously as it had arrived.

Only when the two monks had successfully completed their trip, and amidst celebrations at the World Peace gathering at Seattle, did the Abbot publicly announce the reason for the comet’s sudden retreat. It was the sincerity of the two bowing monks, along with the cultivation of an entire community, that dispelled the imminent danger to all of mankind.

At last the Abbot speaks a few words,

“Don’t believe anything my disciples say. How do you know they haven’t spun these tales out of the blue? Don’t believe anything I say either. Rather, use your own discriminating wisdom to distinguish the true from the false.”

By now it is close to eleven. The hall is still packed. The Abbot transmits the mantra for opening wisdom and the first two of the Forty-two Hands and Eyes Dharma. He bids the crowd farewell and goes upstairs. A stampede follows. Hundreds climb up on stage to grab a flyer with an illustration of the As-You-Will Pearl Hand and Eye. The crowd starts to buckle and sell like a tidal wave. The din becomes deafening as the elation threatens to turn quickly into chaos. The desperation of people hungry for Dharma etches a searing image that burns into our minds.